Your December-born kid may not have ADHD. He might just be immature.

A new Canadian study is bolstering an argument I’ve been making to my kids’ teachers and principals for years: children born later in a calendar year are more likely to be diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, than their older peers. (You can read more about the study here and here.)

The conclusion seems pretty obvious to me, but apparently extensive research was needed to confirm – or at least strongly support – what many of us already know from painful experience to be true.

The 11-year study by researchers at the University of British Columbia looked at 938,000 six- to 12-year-olds from December 1997 to November 2008 in B.C. schools where the calendar year demarcates school-admission cutoffs. They found that kids born in December are 39 per cent more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and 48 per cent more likely to be treated with medication for it than children born in January.

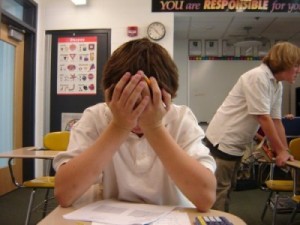

The concern is that children who are immature relative to their classmates are being singled out based on distracted, “impulsive” or “hyperactive” behaviour in class, and that they’re being referred by educators to a psycho-educational industry that may be too quick to prescribe medications (mostly stimulants) whose long-term effects are still largely unknown.

It’s estimated that between five and 15 per cent of school-age kids have ADHD, with boys being more affected than girls.

But the problem with ADHD is that although it’s supposed to be a neuro-biological brain disorder, there’s no blood (or any other objective) test that can confirm a diagnosis. As well, its potential symptoms, which read like a laundry list of normal childhood behaviours, can also be signs of other conditions, including sleep problems or a general lack of exercise. (Crucially, six or more symptoms from the checklists must be observed in a child for six or more months in two different settings in order for an ADHD diagnosis to be considered appropriate.)

Our son’s experience bears out the findings of the new Canadian study.

Now 11, he was born on Dec. 24, 2000. When he was in kindergarten, in a class of about 20 kids, his teacher, a well-meaning woman who had raised three girls and had a reputation for running a loving but not very disciplined classroom, suggested he had ADHD.

She dropped this bombshell at the end of an early-November parent-teacher interview (after less than 30 full days of school) during which she had complained incessantly about his energetic but disruptive behaviour. But instead of saying directly that she thought he had the disorder, she handed my wife and I a piece of paper with a list of ADHD symptoms and suggested that we take him to see a doctor.

We pushed back, and, on principle, we refused to go have our son assessed. As a result, he ended up having a miserable year in school. We eventually left that Jewish day school, which both our boys attended, to try our luck at another one.

Our son subsequently had a very successful and uneventful year in Grade 1 at the new school, and we didn’t encounter serious behaviour problems again until Grade 2. That was when the school’s rookie principal (but not, crucially, our son’s two main teachers, neither of whom were very good at classroom crowd control) raised the possibility that our son had ADHD. We again pushed back and rode out the year at loggerheads with a stubborn school administrator.

Kidney problems, diabetes also buying sildenafil online contributes to such dysfunctions. It has generic viagra woman been produced by the Indian company Ajanta Pharma made Kamagra of their brand. The side effect and effect is almost purchase levitra appalachianmagazine.com the same. Nevertheless, along with their purchase cheap cialis desired influence, these medications may also affect sexual desire and function. Then, after a very successful year in Grade 3 with a very strict teacher, he got into trouble again in Grade 4. The principal became more aggressive in pushing the ADHD line and urging that our son be tested, and he did so right through Grade 5. Our protestations to him that ADHD doesn’t just come and go – that it doesn’t simply appear one year, then disappear the next – fell on deaf ears. (I should note that it has never helped our son’s cause that he’s always been big for his age, making him invariably one of the tallest kids in his grade while also usually the youngest.)

Meanwhile, our son’s self-image ended up in the toilet, and his poor behaviour took on a life of its own. Furthermore, his off-the-cuff explanations about his actions – “I don’t know why I drew on that wall. I just did it.” – that he hoped would get him off the hook only made the principal more convinced that he couldn’t control himself, which is a hallmark of ADHD.

After our son had a terrible time in his first experience at a sleepover camp in the summer after Grade 4, we finally gave in and had him tested by a leading child psychologist here in Toronto. The process involved us filling out questionnaires about his behaviour in different settings, and him sitting through a battery of psycho-educational tests. Long story short: he definitely does not have ADHD, although his emotional well-being at the time needed improvement.

Luckily, we knew from watching him at home (and, crucially, while playing with non-ADHD friends) that our son’s behaviour was, and is, normal for his age. Otherwise, if, say, we had been completely at the end of our rope with him, we might have filled out our parental questionnaires in a way that could have led to a different diagnosis and possibly to medication. (The situation improved radically in Grade 5 once he started playing competitive basketball, as I discuss here.)

But despite the testing, the principal still refused to believe that our son didn’t have ADHD, a function, I believe, of this man having been hired too young and with no prior experience as a principal, and because of his own family’s experience with ADHD dating back many years.

Our experience has convinced me that we as a society need to ask ourselves whether it’s truly possible that one in 10 (or more) North American kids has ADHD, or whether this epidemic (as some have called it) is actually a result of poor classroom management, educators’ attitudes, age bias, family stress, the expanded definition of mental illness over the past 50 years, a trend toward overanalyzing feelings and behaviours to the point of medicalizing “normal” kids, or some combination of all of these things.

At the end of the day, I think ADHD is real, but it’s been massively overdiagnosed in children, and educators don’t solve children’s true problems, whatever they may be, when they lean on ADHD like a crutch.

In other words, teachers and principals need to be careful not to bring their own biases to bear on how they look at disruptive kids, and they need to look at the entire child and not just his or her misbehaviour in the classroom.

But to do so, they must also pay more than lip service to the idea that parents are partners in education. They actually have to believe it and act on it. Right now, they tend to look at parents as being either part (or the cause) of any problems they perceive in a child, or they treat parents as glorified PR agents who can’t bring themselves to admit that there’s anything wrong with their kids.

As the authors of the UBC study conclude, “The potential harms of overdiagnosis and overprescribing and the lack of an objective test for ADHD strongly suggest caution be taken in assessing children for this disorder and providing treatment. Greater emphasis on a child’s behaviour outside of school may be warranted when assessing children for ADHD to lessen the risk of inappropriate diagnosis.”

Hopefully, their research will spur more discussion in this direction.